Share This Article

Thoroughbreds who can demonstrate inbreeding to three different female families within five generations are as rare as hens’ teeth – maybe, even “blue hens’ teeth”.

[su_button url=”http://shop.bluebloods.com.au” style=”flat” background=”#e7f4fc” color=”#2c1f60″ center=”yes” radius=”5″ icon=”icon: exclamation-circle” icon_color=”#2c1f60″ download=”http://www.stallions.com.au/pdfs/2021-booking%20form.pdf”][first published in BLUEBLOODS Issue 1 – 2021. To get this article and more subscribe][/su_button]

It really did not take very long for female family inbreeding (FFI) to become my favorite characteristic within a thoroughbred’s pedigree. I would say it is because it “checked all the boxes”.

Initially it was introduced to me by my close friend and mentor, the late, great Leon Rasmussen whose ‘Bloodlines’ column in America’s primary source of handicapping information, the Daily Racing Form, would long render him the nation’s authority

on what many punters have found to be the most esoteric of considerations when picking the ponies.

Then, there is also the confidence that this approach provides the most interesting and useful way of studying the history and development of thoroughbred pedigrees. This would involve the creation of links and associations that actually help to explain the transmission of important traits, such as racing quality, throughout the last three centuries.

The proof, however, occurs when enough pivotal instances have taken place within the evolution of the racehorse that the auspicious presence of this particular pattern could hardly be just a coincidence and, in fact, represents a causal effect. In other words, over time it can be shown that female family inbreeding, among both runners and producers of runners, significantly outperforms its opportunities, especially when important horse races are reviewed.

And then finally, there is the cherry on top: applying this information to help predict the outcomes of prominent racing venues for both fun and profit. As an example, I can attest to a very gratifying and lucrative return on investment from this approach when placing wagers on the Kentucky Derby and the Breeders’ Cup. All of this was detailed in the 1999 tome, Inbreeding to Superior Females: Using the Rasmussen Factor to produce better racehorses, co-written by Leon and myself and published by Andrew Reichard and BlueBlood’s forerunner, The Australian Bloodhorse Review. Of note, since the book’s original publication, the only change would be an even greater number of winners, whose female family inbreeding patterns within their pedigrees distinguish them from their opposition, particularly in elite events.

The Rasmussen Factor (RF) is a formula. It simply represents the unit used to measure FFI. An individual is considered an RF or is said to demonstrate the RF when inbreeding to a female ancestor occurs, through different individuals, within five generations of its pedigree. Over at least the past twenty-five to thirty years, the percentage of RFs within the overall population of American thoroughbreds has varied but has most often been somewhere between four and five percent. Concurrently, RFs have totalled about seven percent of Grade One winners in the United States. Over this same time frame, the RF population frequency in Europe and Australia has been somewhat higher than in the U.S. but not at all commensurate with the measures of RF success which include 15.0% and 18.2% of the total Group One winners, respectively.

As a rule of thumb, according to noted pedigree analyst Bill Oppenheim, over the last thirty years, the percentage of international Grade/Group One and Two winners has been only 0.80% (four-fifths of one percent) of total named foals. As such, Group/Grade One winners by themselves would amount to well below half of that or roughly one-third of one percent of the total named foals.

Perhaps, it is worth remembering, the most important, if not sobering, caveat that all pedigree considerations account for no more than a third of a thoroughbred’s racing performance(s).

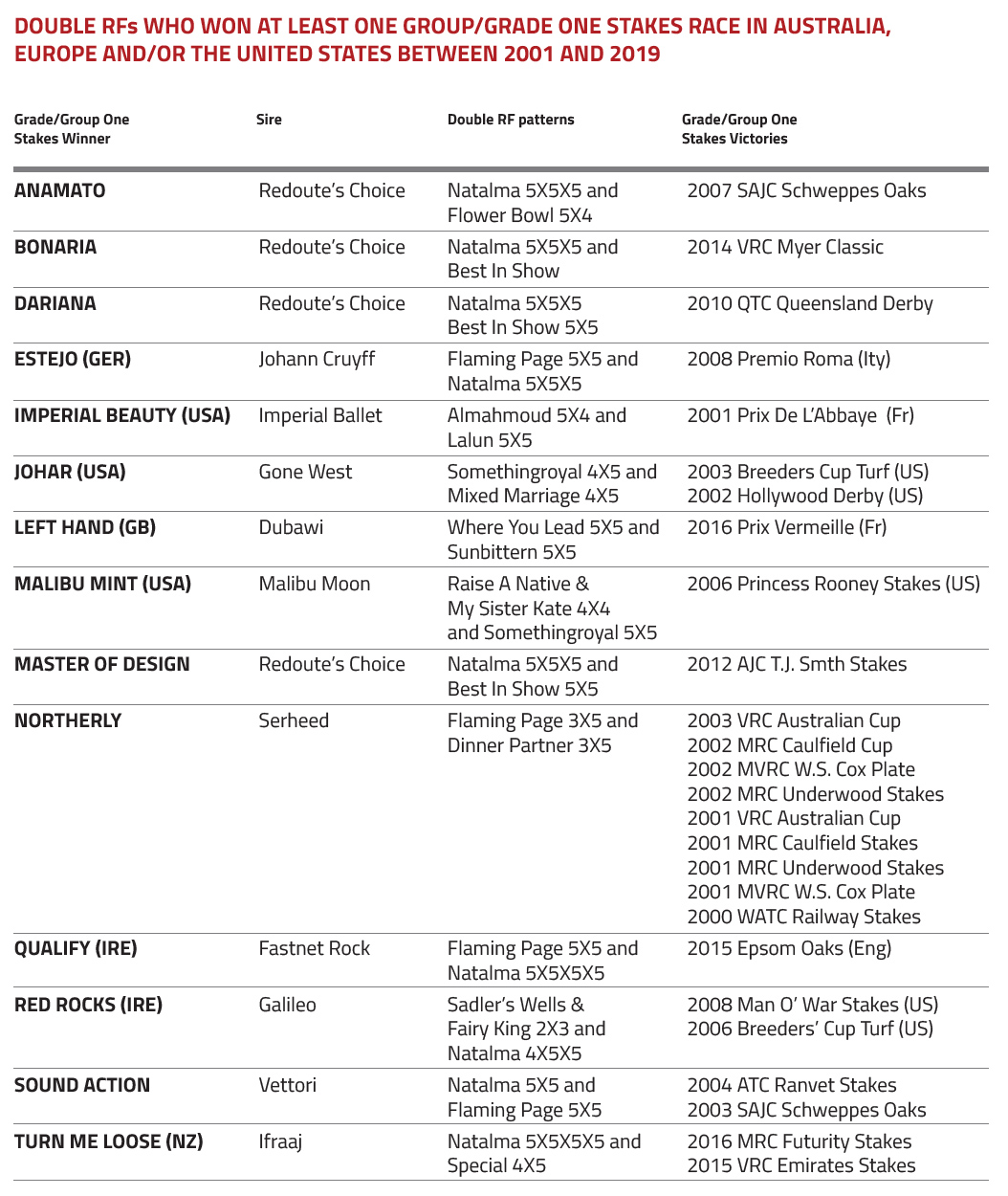

Every so often, a much rarer form of the RF presents itself among pedigrees of note. The DOUBLE RF occurs when the individual’s pedigree is shown to have inbreeding to two different families within its first five generations. It is the “four leaf clover” of RFs. A rough estimate of the number of Double RFs foaled in the Australia, Europe and the United States each year figures to be in the range of only several dozen. These numerical opportunities have been far outweighed by the measures of greatest success they have gained. A striking example is shown in Chart One which lists a total of fourteen Double RFs who have won at least one Group/Grade One Stakes race in Australia, Europe and/or the United States during the first two decades of the twenty-first century. Included are two Breeders’ Cup winners, an English classic winner and an Australian Hall of Famer. And then there is the Triple RF, a thoroughbred individual whose five generation pedigree carries duplications of an amazing three female ancestors, all from different families. These ultra-rare pedigrees might be considered to appear “once in a blue moon”, except a blue moon occurs approximately once every 2 3/4 years, which is mathematically estimated at probably more than five times as frequent as the random foaling of a Triple RF. Even for a very innovative breeder, it would be a formidable challenge to control the breeding rights to a worthy sire and dam whose five generation pedigrees carry the necessary complementary strains to create inbreeding to a trio of female ancestors, each one descending from a completely different family.

Unfortunately, this writer knows of no viable research method capable of filtering through the three hundred-plus year history of the thoroughbred so as to ferret out all the Triple RFs and distinguish the unremarkable from the elite, a group made up of superior individuals.

Instead, an extended, rather arbitrary, search came up with a total of four distinct matings that would issue six Triple RFs who were clearly superior individuals with a total of five full siblings who were clearly not. Each of these remarkable pairings are worthy of review.

AYRSHIRE (GB) & TROON (GB)

Ayrshire was bred by the 6th Duke of Portland (William Cavendish-Bentinck) who had been known for his uncanny fortune in the purchase of prospective broodmares. A high ranking dignitary in the Royal court of Queen Victoria and her son H.R.H. Edward VII, the Duke served as “Master of the Horse”, the guardian of the Royal Stables.

The Duke of Portland’s acquisition of Ayrshire’s dam, Atalanta, was one of his best as she would become a very influential producer and matriarch. Her best mating was with Hampton, England’s 1887 Champion sire which yielded three colts, two of whom won multiple events at top level, one of those the best of his generation.

The pedigree forged by the union of Hampton and Atalanta created a trio of pairings between full siblings. Hampton’s paternal grandsire, Newminster was crossed, 2X3 with his full sister Honeysuckle who serves as Atalanta’s third dam. When a pedigree demonstrates a male ancestor appearing along the tail-male line whose full sister is present along the tail-female line, this unique form of the Ramussen Factor is referred to as the Delta Pattern.

The second and third pairings occurring in the fourth generation of this pedigree include Volley with her full brother, Epsom Derby winner and important sire Voltigeur, as well as the breed-shaping full brothers, Rataplan and Stockwell.

The first of these Triple RFs was the bay 1888 colt Ayrshire, a very good two-year old, winner of the Two Thousand Guineas at Newmarket and the Epsom Derby at three as well as the Eclipse Stakes at four.

The majority of the Duke of Portland’s best horses did, in fact demonstrate FFI. He owned or bred the classic winning RFs Semolina, Amiable, Airs and Graces and Mrs. Butterwick (a double RF).

Ayrshire had a long and successful career at stud including the siring of two Oaks winners.

His 1890 full brother Kilmarnock’s best race was a second place finish to that season’s undefeated juvenile champion, and yet Kilmarnock never actually won anywhere as a two or three-year old.

Ayrshire’s 1892 full brother, Troon was a top class miler at three when he captured the prestigious St. James Palace and Sussex Stakes. A year later he was killed instantly while racing, crashing into the rail with its splinters piercing his heart.

THAIS (GB)

Winner of the 1896 English One Thousand Guineas, Thais was bred by H.R.H. the Prince of Wales who succeeded his mother Queen Victoria to the throne in 1901 as H.M the King Edward VII. As noted above, during the first half of his reign, Edward’s “Master of the Horse” was none other than the 6th Duke of Portland.

The mating of Thais’ parents, the St. Simon stallion St.Serf and the Petrarch mare Poetry yielded just one live foal. As with Ayrshire, Thais’ pedigree demonstrates inbreeding to the full siblings Honeysuckle and Newminster, in this case within its interior. The eternal matriarch Pocahontas is inbred 5X5X5, through two strains of Stockwell and one from of his half-brother King Tom. The third inbreeding pattern was duplication of the important mid-eighteenth century matron Rebecca, 5X5.

Interestingly, King Edward’s own pedigree was a 2X2 Delta Pattern as his paternal grandsire was a full brother to his maternal grandam. Overall, patterns of FFI have been a rather common attribute in the breeding of many royal families. Starting with William the Conqueror in 1066, 19 (forty-five percent) of the pedigrees of England’s 42 ruling monarchs have demonstrated the Ramussen Factor. Five of these were Double RFs. The “sport of kings”, indeed.

SUMITAS (GER)

Perhaps, the easiest way to breed a Triple RF is to develop the sire-producing female families one plans to ultimately duplicate. Such was the case with Sumitas, bred by leading German nursery Gestalt Fahrhof who was responsible for the development of both our subject’s and his sire’s female families.

By convention, all individuals who descend from the same German family have names beginning with the same letter as their common matriarch. Sumitas’ third dam Surata was also the dam of his sire’s broodmare sire Surumu, a German Derby winner and six-time Champion sire (at Fahrhof). All were bred and raced by Gestut Fahrhof.

Love In (GB), third dam to Sumitas’ sire, Lomitas (Ger) was exported to Gestalt Fahrhof where she forged an influential clan that included German Derby winner Lagunas (Ger), sire of Sumitas’ grandam, Surata (Ger).

Sumitas’ pedigree also carried two complementary strains of the (non-Fahrhof) matriarch Kaiserkrone (Ger) who appeared in Sumitas’ pedigree as the dam of Kronzeuge (Ger) and third dam of Konigsstuhl (Ger), a two-time leading sire and the only horse to annex the German Triple Crown.

An undefeated German juvenile champion with facile victories in his first five starts including the 1999 Mehl-Mulhens-Rennen (German Two Thousand Guineas), the British Racing Post referred to Sumitas as “the best horse bred in Germany for many years”. Starting about that time however, victories against Europe’s top company started to become more difficult. Sumitas was performing well but having to settle for runner-up honors in Group One events in Germany, England and Italy.

At age five, Sumitas was sent to the Bobby Frankel barn in the U.S. where he competed on both coasts capturing a couple of nice stakes including the Knickerbocker Handicap, a nine-furlong Grade Two turf event at Belmont Park. Sumitas had two full brothers. Neither of any distinction.

ZABEELIONAIRE AND GONDOKORO

The fourth mating found to yield Triple RFs was that of Zabeel (NZ) and Kisumu in New Zealand. Australian Guineas winner Zabeel was by the foundation sire the great Sir Tristram, a six-time leading sire in Australia. Zabeel, in turn, was a multiple champion sire as both a sire and broodmare sire in both New Zealand and Australia.

Group 2-placed dam Kisumu was purchased for $67,500 as a yearling. From the very beginning of her role as a producer, Zabeel, in New Zealand, was deemed Kisumu’s most appropriate mate. She was delivered to Cambridge Stud for Zabeel’s services every year of her breeding career which was sadly cut short when the Carnegie mare died from an paddock accident in the summer of 2013. Zabeel died two years later at age twenty-nine.

The union was, then, limited to four foals, two males, both gelded early on and a pair of fillies. It was the first two foals who became Kisumu’s two Group One winners.

Zabeelionaire (NZ) was sold for $250,000 at the 2010 Inglis Easter yearling sale and would go on to capture the 2012 SAJC Australian Derby (G1). A year later, Kisumu foaled a full sister named Gondokoro who would win the 2013 BRC Queensland Oaks (G1). The remaining gelding and filly did not distinguish themselves.

This brilliant mating was the brainchild of Trevor and Terrie Delroy, owner of Western Australia’s small but highly successful Wyadup Valley Farm, nestled between the Margaret River and the Indian Ocean.

Zabeel was, in fact, the absolute perfect stallion choice if the goal was to inbreed to the family of the individual (Vali, the tail-female line), while the sire’s family (anchored by Zabeel’s third dam, Derna) is actually a branch of the family of his sire’s broodmare sire, Carnegie. And there’s more. To my mind, this is taking female family inbreeding to an art form.

In the end, FFI is certainly not the “golden goose” of pedigree theory. There are plenty of RFs who can’t get out of their own way. The majority, in fact, will never win a stakes. This probably goes for Triple RFs as well, and yet they are so rare there is really no way to prove just how valuable, much less interesting, their pedigrees have been.

Footnote: We recently compiled a list of distinguished, elite double RFs as per the table right, which includes several distinguished thoroughbreds many of whom excelled both on the racetrack and in their stud careers.