Share This Article

Notwithstanding the notoriety William Allison enjoyed throughout the world of thoroughbred racing and breeding, his business transactions indeed warrant even greater recognition, particularly in regard to their collective shaping of the breed.

Most pedigree scholars who are familiar with Briton William Allison probably associate him with the infamous “Figure System” which he championed following the death of its founder, the Australian C. Bruce Lowe.

Does the Figure System figure?

The system, in a nutshell, allocated numbers derived from the compilation of winners of the oldest English classics, the St. Leger Stakes, Epsom Derby Stakes and Epsom Oaks, grouping them by direct lines of tail female descent. The family with the highest aggregate number of winners or dams of winners became No. 1, the next No. 2 and so on up to 34. Another nine non-winning families were added, making it 43 in all. Several families of preference, #1, #2, #3, #4 and #5 were described as the running families. Moreover, another set of desirable families, #3, #8, #11, #12 and #14, were found to contain the highest number of sires of those classic winners and were identified as the sire families. Basically, accumulation of these nine strains all descending back to their foundation matriarch was the goal.

Many respected thoroughbred breeders, particularly in Europe, took up Bruce Lowe’s Figure System with unbridled enthusiasm, sometimes even enjoying a good deal of success. Elsewhere, the sentiment could be the polar opposite. Several prominent American stud masters became extremely vocal as to the grievous harm being done by the U.S. horse breeders and international buyers who started casting aside the many un-numbered American native families. One gets the feeling from reading different accounts in real time, that the Figure System was a major hot-button issue, especially after it helped to generate the rather drastic Jersey Act of 1913 denying most American blood into the English Stud Book. Allison preferred to call it the “Figure Guide” and seemed to see it much more as a tool, rather than straight dogma.

Lowe’s ideology suffered serious a setback in the late 1930s when Phil Bull, founder of Timeform, conducted a study of what he considered to be the ‘430 worst horses in training’. The results clearly showed that the total number of inferior runners for each family was proportional to its share of previously noted classic winners. As such, the No. 1 family had the highest number of also-rans, the No. 2 family was the second highest and so on. The Figure System was actually not outperforming its opportunities. It held no advantage but was depleting genetic diversity among female families. Thankfully, Bluebloods continues to use them along with the associated (post-Lowe) Bobinski alphabetical letters denoting a family’s major branches.

Despite its many limitations, the Figure System brought necessary order to the investigation of female ancestry. Classification of families has provided researchers with a way that has helped to uncover auspicious similaritieswithin pedigrees.

Lowe’s summarization at the end of his book clearly stated that a successful sire is usually either a tail-female descendant of Families 3, 8, 11, 12 or 14 or strongly inbred to one (or more) of them. This could, in fact, represent the first time an instance of ‘female family inbreeding’ was ever described in print as a distinct strategy. Lowe’s proposition spoke to the power of inbreeding to sire families – a useful approach if ever there was one.

William Allison was a pro-active journalist who loved being a part of the story. Editing and publishing the first and second editions of Bruce Lowe’s Breeding Racehorses by the Figure System made him well known all over the world. He was a prolific writer filling a full shelf of books on the Turf over the course of his distinguished life.

Allison’s first breeding theory, which he proudly shared with his schoolmates, was simply, “Blair Athol’s the blood”. The celebrated son of Stockwell had been trained near Allison’s childhood home in Yorkshire. Decades later, Allison described him as “the best horse I have ever seen, the best bred, best looking, and he beat the best Derby field ever seen, and that too in his first race.” At nineteen, Allison saw Blair Athol capture the 1864 Triple Crown, later becoming a four-time leading sire at Cobham Stud in Surrey where Allison, not coincidentally, would eventually rise from investor to managing director.

Trained as a barrister-at-law, Allison held side gigs at local papers where he picked winners or vigorously opined on current events. He made his first visit to America in 1887 where he had an auspicious meeting with the nation’s soon-to-be preeminent owner and breeder of thoroughbreds, James R. Keene.

In 1891 at the age of forty, William Allison was hired by the The (London) Sportsman with the exalted title of “The Special Commissioner”. He always thoroughly enjoyed his many journalistic skirmishes with his counterpart, the highly esteemed J.B. Robertson (“Mankato”) from The Sporting Chronicle. His columns regularly featured contests challenging his many readers on exactly why he selected the mares he did at recent sales. He was also regularly caught, unabashedly hyping whatever commercial project he was involved in at the time. He later responded, “who could (possibly) write twice or three times a week, for thirty years without committing a lot of nonsense to paper at one time or another?” Notwithstanding the pomp, the biggest regret Allison had was not attending Veterinary school, “not in order to practice, but to be able to write on the racehorse with a confidence lacking the layman”. But William Allison was a man of considerable charm and character and with no interest in betraying confidences he was rewarded with privileges of information to apply to his trade(s).

The creation of American sire power

Mostly on account of his lofty position at The Sportsman, Allison’s role as a bloodstock agent began to take off in late 1891. His previously dormant one-man operation known as the International Horse Agency and Exchange, Limited suddenly received a multi-year commission from J.R. Keene to select dozens of broodmare prospects at the December Newmarket sales, get them back in foal to a top stallion, and export them to America. Over the next three decades, Allison’s services were engaged to supply some of America’s most influential breeders with the most compatible English broodmare prospects he could find. Horsemen like August Belmont II who bred Fair Play and his magnificent son Man o’War. And Sam Riddle, Big Red’s lucky but clever owner.

Allison paid very little attention to the race records or racing class of the broodmare prospects he acquired for his clients or Cobham. Instead, his emphasis was clearly on pedigree, in particular the mare’s immediate female family.

It was certainly appropriate for Allison to be commissioned to put together a small harem of English broodmares for Man o’War since he was responsible for procuring three of the super-horse’s four grandparents for Jockey Club chairman August Belmont II. This is well demonstrated within the pedigree of Man o’War’s best son, War Admiral.

What is particularly peculiar is that Allison never made, in his later years, any kind of summary to establish the collective success his importations to America had enjoyed. For whatever reason, boyhood tales would take up more room in his memoirs than his overwhelming effect on the American (World) Thoroughbred. In Allison’s mind, everything had been sufficiently documented in his columns for The Sportman. In Memories of Men and Horses from 1922, he stated “The International Horse Agency and Exchange Ltd. has done an enormous business in all these years, and it would be tedious to recapitulate even the leading items”.

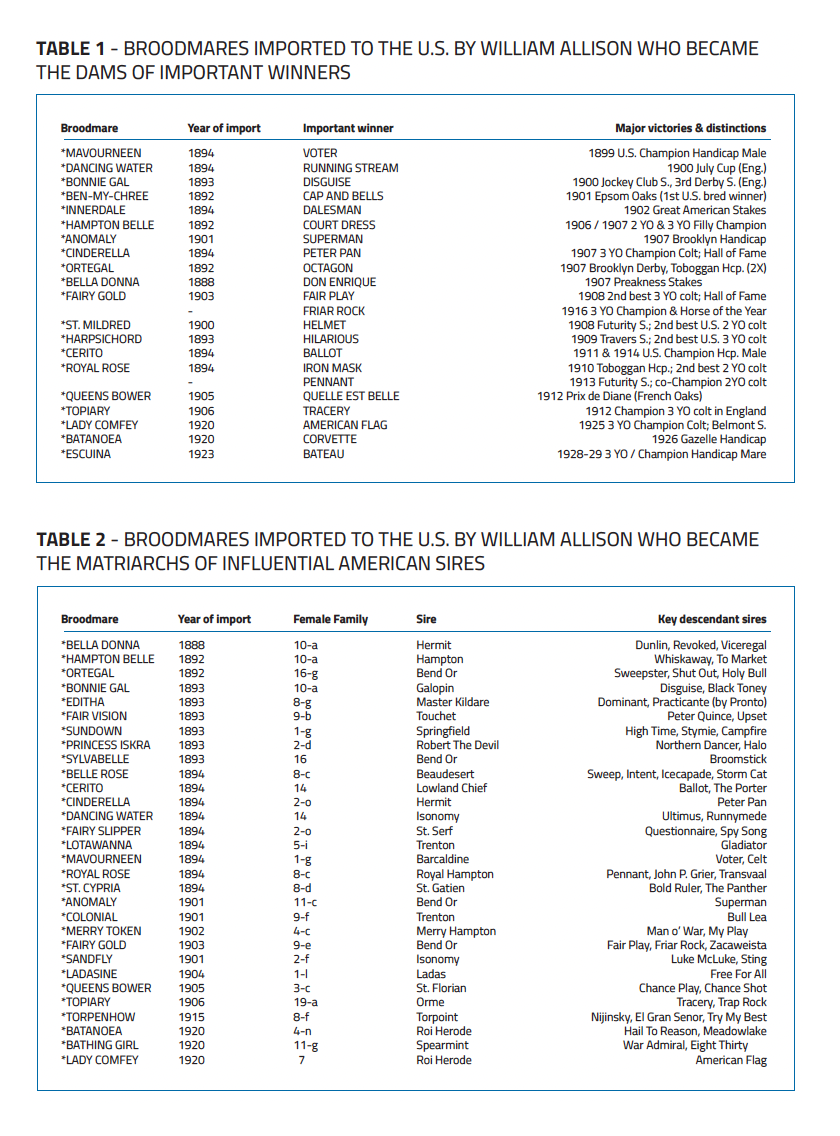

Table 1 lists Allison-imported broodmares who foaled American-bred champion quality offspring. It is a compendium of success. Table 2 features the Allison-picked broodmares who became matriarchs to (multiple) influential American sires. It is a record of Allison’s contribution of families that provided America with its most influential sires. With the aid of color, Tables 3, 4 and 5 highlight all of this in vivid fashion by sire line.

As shown, Allison was uniquely responsible for most of the families who issued “the triumvirate” of Domino, Ben Bush and Fair Play, America’s three great sire lines during the early part of the twentieth century. There was also significant involvement with several other lines of the time including Rock Sand and Voter. Mid-century super sire Bull Lea traced back to an Allison broodmare. Families that were initiated by one of The Commissioner’s broodmare imports went on to produce key members of the Nearco explosion during the second half of the last century, as shown in Table 5. Both Northern Dancer and Bold Ruler traced in tail-female line to an English-bred mare selected and exported by William Allison.

In 1915, Torpenhow, by the Trenton sire Torpoint, was collared by Allison and shipped to Wickliffe Stud in Kentucky. Decades later, this single broodmare prospect started appearing as family matriarch in the pedigrees of a particularly large group of Northern Dancer’s best sire sons including Nijinsky II and Storm Cat (see Table 5).

The apex of Allison’s profound influence is well illustrated in the pedigrees of the four American Triple Crown winners from the late 1930s to the mid-1940s, War Admiral in 1937, Whirlaway in 1941, Armed in 1944 and Assault in 1946. Allison’s select mares who appear have been highlighted in bold red. Sires who had transactions and/or mating decisions that involved William Allison are noted in bold blue.

War Admiral’s pedigree was filled with important ancestors who were descendants of Allison mares including the families of his sire, his dam, his grandsire and his broodmare sire.

Whirlaway had an English sire, so there were none of Allison’s imports involved. On the bottom side, the sires of his first and second dams were both descendants of Allison mares.

Armed’s pedigree is chock-full of Allison mares. Running Stream has been underlined in the fifth generation as she is a daughter of the Allison mare, Dancing Water. In total, this pedigree carries a remarkable seven different mares who were purchased and delivered to the U.S. by our subject.

Finally, Assault’s pedigree is yet another that features a marked accumulation of Allison’s mares. Elf has been underlined in the fifth generation as she is a daughter of the Allison mare, Sylvabelle, which makes a total of six distinct female representatives.

The decisions, in fact, made between the 1890s and the 1920s by William Allison led to much of the shaping of the twentieth century American thoroughbred which, in turn, would cause a reshaping of the international thoroughbred.

Allison had similar arrangements with horsemen in France for whom he bought and dispatched English mares. Two of them became the dams of legendary turn-of-the-century filly La Camargo (1898, Fr.), and Horse of the Year and three-time leading sire in France, Perth (1896, Fr.) whose obscure sire line survived into the 1960s.

Selling English classic winners

By the early twentieth century, Allison had become one of the premier turf writers in the world with his columns gaining international exposure, including America’s Daily Racing Form. When 1903 English Triple Crown winner and foundation sire Rock Sand became available for purchase upon his owner and breeder’s death, August Belmont was ready to pay the $125,000 price crediting Allison’s enthusiastic articles for generating a strong interest in the celebrated young sire. Not only did Allison broker the sale of Rock Sand but he also spent $10,000 for Topiary, by Orme, an impeccably bred broodmare prospect who The Commissioner considered a perfect mate for Belmont’s new flagship sire. Allison delivered the two on the same ship, their union ultimately producing Rock Sand ’s best offspring, Tracery, a champion three year-old in England and like his sire, of chef-de-race influence. Twenty years later, Allison reappeared to handle Tracery’s return

to England from Argentina when his son Papyrus won the 1923 Epsom Derby. It turned out to be a first-of-its-kind syndicate sale involving famed European horsemen, the Aga Khan and Marcel Boussac.

Between 1897 and 1903, England produced four Triple Crown winners, three of whom were later sold as stallions with Allison’s involvement. 1897 English Triple Crown winner Galtee More was purchased for £22,500 by Allison for the account of the royal Russian family. Not for business, but “as a friend”, Allison recommended 1900 Triple Crown winner Diamond Jubilee to Senor Correas, president of Argentina’s Jockey Club and Stud Book who made him his premiere stallion and was rewarded with four sire titles. During this same period, Allison sold 1902 Epsom Derby winner Ard Patrick to the Graditz Stud in Saxony, Germany where he was a three-time sire champion. Galtee More relocated and joined him at Graditz a year later where he too won a German sire title.

Allison’s overall success had a lot to do with his love of travel. The Yorkshireman spent a good deal of time on ships. Visiting most of the world’s major racing and breeding centres allowed him to make friends, business connections and contacts within the media and other sources of information. Travel served to expand his column’s global reach. Ships, too, were where he wrote (and edited) many of his well-received books.

Australia and Gainsborough

Allison also developed a productive clientele in Australia where he was instrumental in the 1,100 guineas purchase of Bill of Portland (1890) on behalf of Geelong’s legendary St. Albans Stud. Bill of Portland, Australia’s first St. Simon horse, was only available for export after becoming a roarer at age four, rendering him a dubious stallion prospect. He arrived in Melbourne in June of 1894 and quickly became an unmitigated success siring his new land’s champion three year-old colt in each of his first three seasons. The third

of these, Maltster became Australia’s leading sire five times.

In 1895, Trenton, the fourteen year-old Musket stallion who was already a two-time champion sire in Australia was purchased by Allison for £3,500. In this instance, the bloodstock was intended for Allison’s own interests, the rebuilding of a stallion program at Cobham Stud where he had recently taken charge. Under Allison, the majority of his stallions were the sons and grandsons of Musket as well as Allison’s favourite, Blair Athol who earned four English sire titles, three at Cobham in the 1870s when the young lawyer was slowly accruing its stock. Trenton failed to perform as well as he had Down Under, but several of his daughters were, as previously described, dispatched by Allison to his U.S. clients where a number of them became influential broodmare and matriarchs, (see Tables 1 and 2).

Actually, the most important of Trenton’s English-bred fillies was Rosaline (1901), out of a Bend Or mare, who was so small her owner and breeder, celebrated horseman J.B. Joel, gave her away to charity. Soon thereafter, she was picked up at auction for 25 guineas by none other than William Allison. But after she grew several inches, Allison chose to get her in foal and pass her on in 1904 for 200 guineas. Three years later, Rosaline foaled 1910 Epsom Oaks winner Rosedrop, who in turn, produced Gainsborough, 1918 English Triple Crown winner and a dual sire champion, who got Hyperion and his mighty male line dynasty. Allison wistfully added, “(it is) Gainsborough who (now) fills at a 400 guineas’ fee”.

In a second similar tale, Allison was reminded of his purchase of an obscurely-bred seven year-old mare named Lowland Aggie at the Newmarket December sales for 35 guineas. Having eventually taken his profit, Allison watched as the same mare foaled England’s 1911 two year-old champion and good sire Lomond, by Desmond.

This was the exception. Allison was much more accustomed to choices that scored big for his clients, not someone else(s). In November 1896, Lillie Langtry, a beautiful and prominent actress on the London stage came to William Allison’s office and asked if he could find her a good horse. Allison answered with pure prescience when suggesting he could furnish the starlet with the winner of Newmarket’s eighteen furlong Cesarewitch Handicap for a sum of £2,000. In February of 1897, Australian five year-old Merman, by Grand Flaneur, reached England and in October summarily captured said race. Over the next three seasons, Merman triumphed in an assortment of the most prestigious two-mile plus fixtures including the Ascot Gold Cup. Merman’s British exploits were rewarded in 2016 with his induction into the Australian Racing Hall of Fame.

Most of Allison’s detractors, usually vocal opponents of the Figure System, might not have agreed, but The Commissioner’s many activities really did dovetail quite well with the variety of positions he held, creating one of the greatest bodies of work in Thoroughbred history. By any measure, he has been highly underestimated, especially in America.

When William Allison passed in 1925, The Bloodstock Breeders’ Review wrote, “it has been given to few men to live a life so full of interest and adventure, and we may be sure that he enjoyed every minute of it.”